Antimicrobials: Handle with Care

Article by Chibuike Alagboso (Nigeria)

I consider myself someone who rarely falls ill. This belief is usually associated with poor health-seeking behaviour. Yet, it’s something that a lot of people say in Nigeria, especially men. But sometime in August this year, I had to seek medical help because I had severe generalised body pains and fever. At the hospital, the medics quickly gave me an injection to help with the fever and took my blood sample for laboratory investigations. A couple of hours later, I got relieved and went in to review the test results with the doctor. I had elevated white blood cells, which shows signs of an infection, so he prescribed antibiotics.

I raised concerns about taking antibiotics without knowing the source of the infection. He explained I would require a blood culture and that could take days. According to my health insurance provider, if he took that treatment route, he couldn’t have prescribed medications until the culture results are out. My doctor proceeded with prescribing broad-spectrum antibiotics. While I understood this made sense for my specific case, I am also well-aware of the importance of carrying out cultures and the dangers of the indiscriminate use of antibiotics and its real-life implications.

Antibiotics have saved millions of lives since British scientist Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin in the 1920s. But the bacteria that antibiotics fight are living things constantly battling to stay alive. This causes them to change their physiological and chemical configurations, usually referred to as mutation to render the antibiotics ineffective. When this happens, it’s referred to as antibiotic or antimicrobial resistance (AMR). AMR is regarded as one of the top 10 global public health threats humanity is facing. Several efforts are being put in place to address it including the annual World Antimicrobial Awareness Week to raise awareness and sustain the momentum to mitigate it.

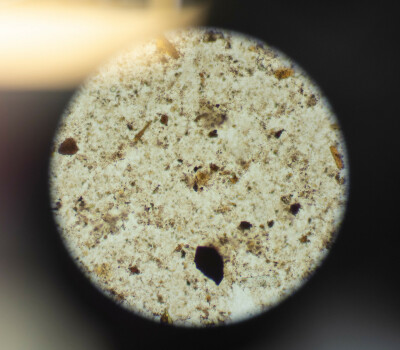

Antimicrobial resistance undermines the body’s immune system’s ability to fight infections and can lead to different complications in vulnerable patients undergoing various treatments. Microscopy and culture are important to combat AMR in medical practice because they help health professionals to identify the specific microorganism causing an infection. Antimicrobial susceptibility tests determine which antimicrobial medication is most effective against identified bacteria. The equipment and infrastructure needed for this laboratory investigation is usually expensive, limiting access to effective treatment in resource-limited settings such as low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Clinical bacteriology laboratories are sparse in LMIC. Equipment and working material such as quality-assured culture media for culturing bacteria are often not available, because of the high cost and supply chain problems.

Professor of Microbiology at the University of Abomey-Calavi in Benin, Dissou Affolabi said the high cost of equipment is challenging for managing bloodstream infections because it is important to diagnose quickly to enable physicians to give the right medications. Affolabi, who doubles as the head of the microbiology laboratory at his university’s teaching hospital is also the principal investigator of SIMBLE, a project working to address this problem. SIMBLE stands for simplified blood culture system and aims to introduce diagnostics that are better adapted for sub-Saharan Africa.

The project is a collaboration between the Belgium-based Institute of Tropical Medicine (ITM), Ghent University, and Université Libre de Bruxelles. Commissariat à l'Energie Atomique et aux Energies Alternatives in France, Reactivos Para Diagnóstico in Spain, Affolabi’s university hospital in Benin and the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire Yalgado Ouédraogo in Burkina Faso are also part of the consortium.

“With Ghent University, we developed a small device that can improve and speed up the diagnosis of bloodstream infections”, says SIMBLE project coordinator from ITM, Dr Liselotte Hardy, a post-doc researcher in the Unit of Tropical Bacteriology of the Department of Clinical Sciences. With her unit’s work mostly focused on AMR surveillance, Hardy said they help partner institutions in different countries build diagnostic capacities. While the SIMBLE device is meant for low-resource settings with environmental conditions for which the specialised blood culture automates are not adapted, it is not meant as a replacement for all settings. “It will never perform better than automates used in high-income countries,” Hardy said, “but it will be better adapted to the context where it will be used.”

In addition to implementing a simple inexpensive way to evaluate bacterial growth in blood cultures, another tool for bacteria identification is currently also being developed and will be used in the SIMBLE project, says Affolabi.

The production container will be used to locally produce culture media in a quality-controlled way and was jointly developed by project team members from Barcelona, Belgium, and Benin, said Hardy. This helps ensure sustainability. When the project is fully operational, they will be able to produce the media locally.

This is very important according to Hardy and Affolabi, because most culture media are currently imported from Europe and given their short shelf life, there is limited time to use them before expiring. But doing this in-country requires the right competence to prepare, control, and store the media, Affolabi said. “Doing this and certifying the quality of the media is not easy for laboratories in Benin,” he said, adding “which is why we proposed to have a comprehensive container lab in this project that can house everything”.

But it didn’t come without its fair share of challenges as with everything worthy of making a significant impact. Starting with the logistics of importing the container and finding an ideal spot to serve as its home in the hospital, said Affolabi. Before that, getting all equipment fitted into the container, transporting and clearing it with customs also caused some delays. This is in addition to the logistical challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, Hardy said.

But despite these, Affolabi said the project makes him happy and enthusiastic about the possibility of better diagnosis and management of bloodstream infections. Even more exciting for him is the potential to export this capacity to other African regions. With five people already having gone through training for trainers, the university is ready to take ownership once the project is fully deployed, Affolabi noted.

While institutions like the ITM are supporting these efforts to develop better diagnostic tools and local capacities, it’s also important for countries and regional public health institutions like the Africa CDC to invest in research and development of innovations that address country-specific challenges. As Affolabi says, “without innovation, we will copy other people and when you are copying other people, it will be hard to go faster than the people you are copying”.

So how can we stick to the best practice of prescribing antibiotics based on the laboratory testing, when in LMIC there are often challenges with the availability of the right medication and diagnostics? “In fact, antibiotic and diagnostic stewardship is crucial to convince health professionals to prescribe what is needed and what is available,” Hardy says.

As for my illness, I didn’t do the blood culture. The doctor prescribed the antibiotics, and I made sure I finished the dosage as instructed by the pharmacists, understanding the importance of completing the full course of treatment to avoid antimicrobial resistance. In a week or so, I felt better.

Spread the word! Share this story on