"I realised that I could not help as many people as I wanted by sitting behind a desk in a hospital"

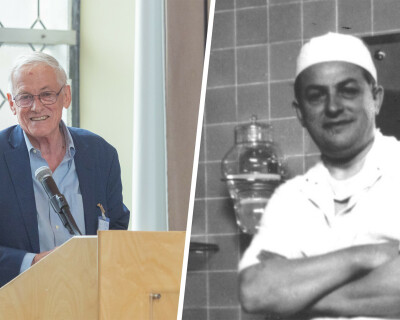

Legacy funding in practice. Please meet Dr Moïse Saa Denah Tenkiano, medical doctor, Health Programme Manager and Romain De Cock Scholarship grantee currently hosted at ITM. After Utibe-Abasi Dominic Edet (Nigeria) and Dr Miora Henintsoa Rajaonarivony (Madagascar), Moise is the third student in a row to benefit from a scholarship that is financed by the late Firmin De Waele, honouring the De Cock family's commitment to global health.

Good afternoon, Moïse, happy to have you here. You are currently enrolled in the Master of Public Health (MPH) programme at the Institute of Tropical Medicine. Why did you decide to become a medical doctor? What motivated you to pursue advanced studies in tropical medicine?

MOÏSE I graduated with a medical degree in Guinea, Conakry, my hometown. Quite early in my career, I realised that I could not help as many people as I wanted by just sitting behind a desk in a hospital. So, after working as a doctor in a hospital, I decided to embrace a new career in public health.

Then, when Ebola struck our country in 2014, the Ministry of Health called on all medical doctors to join the fight against Ebola. I was recruited by the USA-based international NGO Helen Keller International and trained by WHO to become a certified trainer in infection prevention and control (IPC) in the context of Ebola. My role involved training healthcare professionals on IPC and implementing Ebola surveillance in upper Guinea. I was fortunate that there were few cases of Ebola in the region. My involvement in the outbreak led me to join the Neglected Tropical Diseases Programme in 2016 as a Programme Assistant at Helen Keller International.

In this role, I had the opportunity to travel to remote areas and meet people facing severe health problems. Often, these issues involved infectious diseases such as trachoma, which causes blindness. This experience deeply affected me emotionally, as I witnessed the suffering of patients with eye diseases like trachoma.

While working with Helen Keller International, I quickly realised that acquiring core competencies in international cooperation and humanitarian aid would enhance my ability to make a broader impact and advocate for those who are left behind. Consequently, I completed a Master’s degree in International Cooperation and Humanitarian Aid from the Kalu Institute in Spain. In November 2020, I was approached by a UK-based international NGO, Sightsavers, to join their team as a Programme Coordinator. I accepted the offer and worked with them for several years.

I am proud to say that, with Sightsavers and under my coordination, over 2,500 surgeries to combat trachoma were performed in Guinea, leading the country to the elimination of trachoma as a public health problem. I am happy that I was able to serve my country in this fight. By the end of 2025, Guinea is expected to be free of trachoma, with only a few isolated cases remaining. Of course, this success is also due to political commitment and investment in national health programmes, but I am personally very proud to have played a pivotal role.

A successful trachoma surgery performed on an albino person, who are highly stigmatised in my country, led to a breakthrough after the story got published by Sightsavers on the occasion of World Neglected Tropical Diseases Day in January 2022.

In 2023, I received a certificate of recognition for my successful implementation of the trachoma programme in Guinea. To top up things, I also completed training in project management essentials with the George Washington University in the USA. I worked with Sightsavers for four years before deciding to pursue further studies at ITM.

Trachoma

Trachoma, caused by the bacterium Chlamydia trachomatis, is the leading infectious cause of blindness in the world.

More than 100 million people live in trachoma-endemic areas, with children in Africa being most affected.

Elimination efforts are guided by the WHO-endorsed SAFE strategy: Surgery, Antibiotics, Facial cleanliness, and Environmental improvement.

Thanks to the sustained commitment of the government, partners and local communities, more than 6 million Guineans now live in areas where trachoma is no longer considered a public health problem.

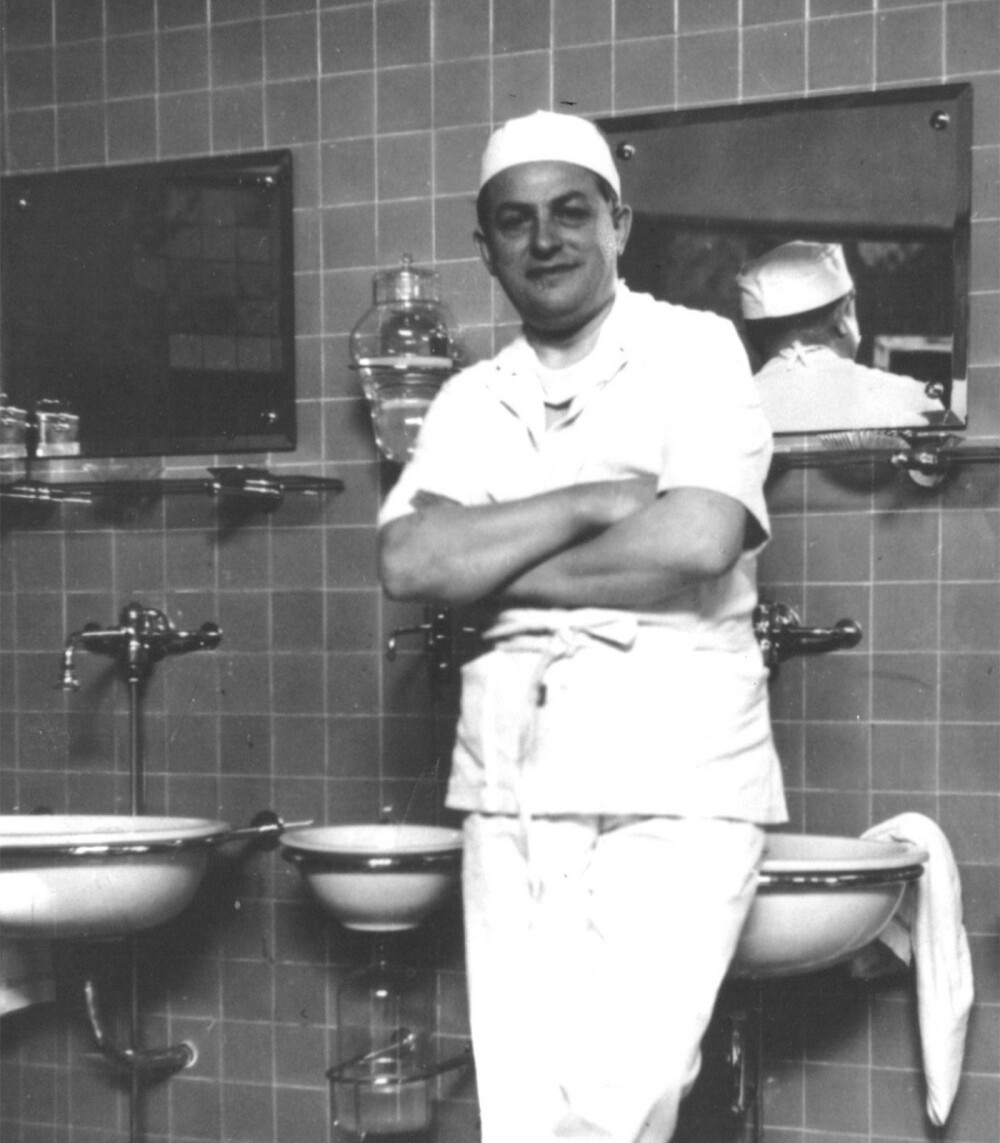

Dr Romain De Cock was known for his dedication to surgery and international health. There seems to be many parallels between you and Dr De Cock. How do you feel about that?

MOÏSE Actually, my father wanted me to become a surgeon. It was his dream to see me perform this profession. He deeply respected medical doctors and had great faith in them. So, I started medical studies, but my real wake-up call came when I left Conakry to perform surgery in remote areas. Out there, people reacted very differently to treatment: they were skeptical of medical interventions. I had to develop new skills to convince them to accept surgery. It was a challenging but incredibly rewarding experience. Seeing the impact of successful treatment and hearing a patient’s heartfelt "thank you" is something that goes beyond words. It reaffirmed my calling.

As a recipient of the Romain De Cock Scholarship, how has this opportunity impacted your academic and professional trajectory?

MOÏSE Coming to ITM is more than just fulfilling a dream: it is a true gift! I applied to several programmes and was actually accepted at three different institutions in Europe. But when I received my acceptance letter from ITM, my family and I spent the entire day celebrating because being admitted to ITM is what I wanted the most. I turned down the other offers without hesitation. My ultimate goal is to serve humanity, but first and foremost, my country (laughs)!

What made you choose ITM?

MOÏSE The sense of community among the MPH fellows and the fact that the professors truly understand the African context. Antwerp is a part of Africa! Most of our case studies are African cases, and they cover the whole spectrum of public health challenges we actually face. The professors teach you the reality, provide the right skills and prepare you to serve humanity as a scientist and professional public health practitioner.

Could you elaborate on your current research at ITM? What specific health challenges are you addressing, and what do you hope to achieve?

MOÏSE My research focuses on the acceptance of medical surgery among women. I observed clear disparities in the acceptance of trachoma surgery: female patients are less likely to agree to undergo treatment. My study aims to identify the barriers preventing women from seeking surgery. In my country, women are responsible for taking care of their families and often put their social responsibilities ahead of their own health. This creates quantitative disparities, but my research mainly focuses on the qualitative aspects of this very topic.

(Moïse shows a video) Here, you see a woman refusing treatment. To change her mind, we had to visit her village and speak with the men in the community. Women in my country feel a deep sense of duty towards their families, even when it negatively affects their own well-being.

How do you envision your research contributing to the healthcare landscape in your home country? What are your professional goals post-graduation?

MOÏSE My studies and profession allow me to play an active role on the African continent, and that is exactly what I want to do. I am open to working within international projects, either in Africa or abroad, wherever I can make the most impact.

Could you share any challenges you've faced during your academic journey and how you've overcome them?

MOÏSE Leaving my family was the hardest part. I have two young daughters, and I spend hours on the phone with them. They always ask the same question: "Papa, où es-tu ?" And of course, adjusting to the weather was tough, but I got used to it!

What advice would you give to aspiring students from low- or middle-income countries who wish to pursue studies in tropical medicine?

MOÏSE Be consistent, set clear goals, work hard, and go for it. Don’t just dream: make a solid plan. Also, language skills are crucial. Personally, I went to Ghana to improve my English. My wife, an environmentalist, trained her English there, and I definitely wanted to keep up with her English skills!

Any final thoughts?

MOÏSE Yes, a profound thank you to my professors at ITM, my fellow MPH students who have become my friends, my family, and the De Waele/De Cock families, whose generosity made this scholarship possible. The best word I can offer them is a heartfelt "thank you".

Romain De Cock scholarship programme

To honour the legacy of Dr Romain De Cock, we launched the Romain De Cock scholarship, awarded yearly to a student from a low- or middle-income country to enrol in a master 's programme at ITM.

Would you like to know more about Moïse?

Moïse recently published his book L’ombre de l’espoir with L’harmattan Editions. You can order it from Fnac.be.

Statement by Kevin M. De Cock

I was very pleased to read this interview with Moïse Tenkiano whose career and aspirations are very much aligned with the vision of the Romain De Cock Scholarship. My father (RDC) was a general surgeon of the old school, meaning he covered all aspects of surgery with the possible exceptions of cardiac and neurosurgery. He was committed to his work in Flanders but recognised the need for international collaboration and exchange of information.

We established the scholarship with generous funding from Firmin De Waele, a cousin. In the evolution of global health over past decades, it became understood that clinical services form an integral part of aspirations for “health for all” and universal health coverage. The scholarship builds on this, aiming to link public health with service delivery. Surgical services – defined broadly, and ranging from anaesthesia to ophthalmology, obstetrics, infection prevention and control, antimicrobial resistance, and more – have received less attention than programmes for the major infectious diseases that I have worked on.

Moïse’s interview speaks to all elements behind the scholarship. He has paid his professional dues in field work in difficult places, dealing with challenging health issues. That experience is essential and provides a sound basis for obtaining maximum benefit from time at ITM. I wish Moïse well with future endeavors, including his literary efforts (I am very impressed that he has published a novel!). Good luck, Moïse, and I hope you will see your daughters soon!

Kevin M. De Cock

MD, FRCP (UK), DTM&H

Spread the word! Share this story on