"I'm one of those idealists who graduated with the goal in mind: 'That's where I want to work!'" - Dr Liselotte Hardy

What is SIMBLE?

LISELOTTE With the SIMBLE project, we are testing a new system for blood cultures. Through those blood cultures, you can detect bloodstream infections. The project name stands for 'simplified blood culture system'. Very concretely, with this project we are testing a new system adapted to the needs in Africa.

What exactly are bloodstream infections? Why are they dangerous?

LISELOTTE A bloodstream infection can occur in a very banal way. For example, because a bacterium got into your blood via a wound. Normally, your immune system will remove the bacteria, but sometimes things go wrong and the bacteria start to multiply. You then get an infection. Such a blood infection can lead to sepsis, which can be life-threatening.

What role do blood cultures play in the diagnosis of bloodstream infections?

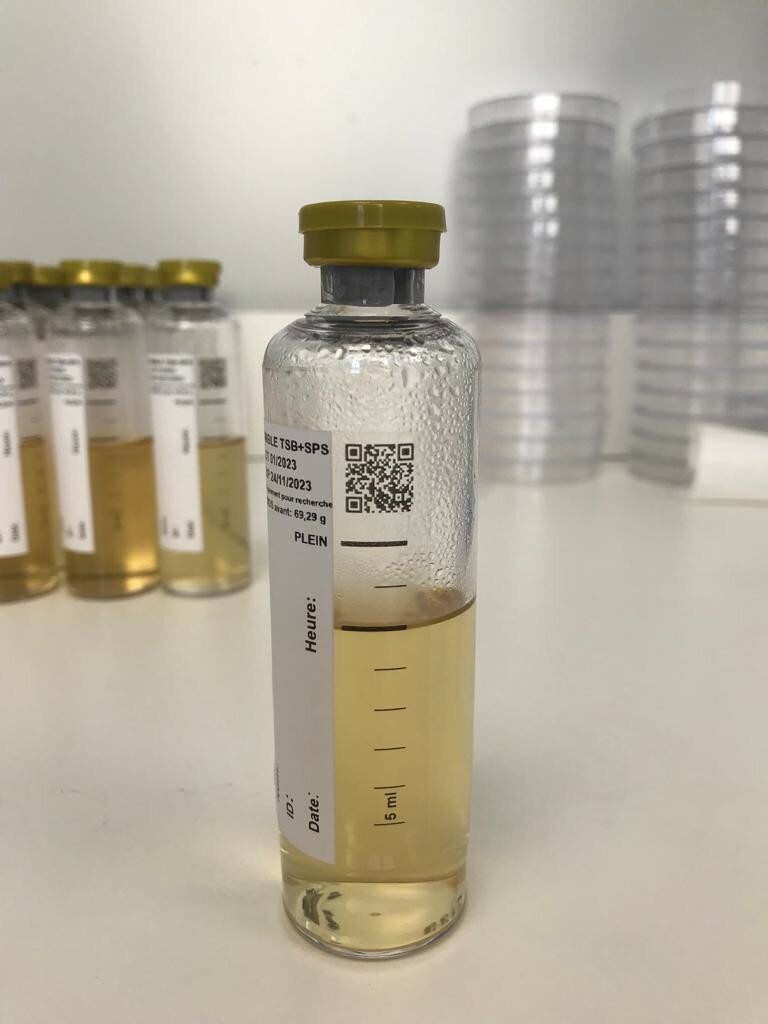

LISELOTTE Suppose you have a high fever and go to the hospital. Among other things, blood is then drawn in a blood culture bottle. The bottle also contains a so-called growth medium. The bottle is then placed in a machine with the right temperature (body temperature) to allow the bacteria to grow. If bacteria begin to grow, there is a diagnosis of a bloodstream infection. Next, the microorganism which is causing the infection has to be identified and the best way to treat it determined.

This system works well in the North, but it is difficult to apply in low-income countries.

LISELOTTE Indeed. The machines are very expensive to buy and to maintain. If spare parts are needed, it costs almost as much to repair them as to buy a new one. If the equipment has to be shipped to Africa the the price multiplies by two or even three. Besides, the manufacturers are not eager to go there for maintenance.

The equipment is also not well adapted to the needs of laboratories in the tropics. The devices do not cope well with high humidity and temperature. The blood culture vials have to stay at 35 to 37 degrees, but if the ambient temperature is higher and there is no air conditioning available, things go wrong. Moreover, if the laboratory is too dusty, there are chances of this dust getting into the blood culture machine and the machine starts failing as a result.

Blood culture vials containing the required growth medium also have a limited shelf life. Once they are on site, they sometimes last only a few months because it takes so long to get them there.

How are such tests currently carried out in Africa?

LISELOTTE They detect bloodstream infection mainly visually, without the help of a machine. We buy the vials and ship them to our partners in Africa. They put the vials in a regular incubator and then check two or three times a day for bacterial growth.

With the SIMBLE project you are trying to provide a solution for this

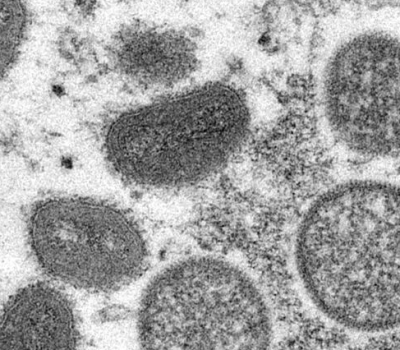

LISELOTTE We have developed the Bactinsight system, which consists of two parts. The first part is a new device, the Turbidimeter. It is a simple box with an LED lamp and two sensors, into which the bottle is placed. The light bulb sends a beam of light through the bottle. The sensors interpret the beam for 'turbidity'. The cloudier, the more bacterial growth.

In a second step, we use a lens-free microscope developed by our partners in Grenoble (CEA). Once bacterial growth is determined, we place a drop on a petri dish. The lens-free microscope sits under the dish and takes a picture every 30 minutes. That allows us to identify the bacteria.

But you have also developed another important innovation - blood culture vials.

LISELOTTE Shipping the vials is very expensive and very slow. During a previous project, we analysed the different commercially available growth media to know which ones are most suitable for growing the bacteria we see most in the field. We were able to narrow it down to a very simple medium based on two powders that you mix together.

You also looked at how the vials, medium and petri dishes can be produced locally.

LISELOTTE We have a project partner in Barcelona who produces vials, among other things. Through them, we developed a shipping container in which we had a mini-factory built. So we have a mobile production environment that works entirely according to current standards, allowing clean and safe work. We shipped that to Cotonou, where it is now being used.

This project has an impact on antibiotic resistance. How big is the problem in Africa?

LISELOTTE If antibiotics are taken unnecessarily or incorrectly, resistance grows. In Europe, this can be addressed to some extent by adjusting the treatment based on the diagnosis. In Africa, they often have to make do with what's in the cupboard; not every antibiotic is available or affordable there. Because of globalisation, everything obviously gets to us, including the germs that are multi-resistant. And then we in turn have to face the same problem. The start of good and efficient treatment starts with better and faster diagnosis. And that is where SIMBLE tries to play its part.

How much of a difference can SIMBLE make?

LISELOTTE We are already noticing that there is more awareness. We now have three study sites, two in Benin and one in Burkina. More technology is coming in, more people are being trained in diagnostics and treatment, but new research is also coming out. On a global scale, the project may not be that big, but we see a lot of interest and we hope it can also be a start of more local production in Africa and Asia. For example, our partner Dissou Affolabi in Cotonou has taken control of the process and is working completely autonomously. That is great to see and also teaches us that we are not always needed.

It is continuing the philosophy of 'Switching the Poles', where we seek equal exchange with our partners in the South.

LISELOTTE We wanted to start the study in Burkina Faso, but the government imposed a travel ban. In the end, we suggested to our partners in Cotonou to train their colleagues in Burkina. They can do that as well as we can.

Will the development of SIMBLE have a direct impact on patients?

LISELOTTE Not everyone can afford a blood test. In fact, costs are usually passed on to patients. We can absorb that in the study. And by introducing the study, more patients can get a diagnosis. For example, since the study was launched in Burkina, we have seen an extremely high increase in sample collection. The number of positive diagnoses is more than double what we would expect. Such an increase tells us that even more samples should actually be collected at the hospital level. With local production, this can be done at a fraction of the current price.

How is the project funded?

LISELOTTE By EDCTP. This is European-African funding, where both European and African countries contribute. If you contribute, you get to participate as a country. We have partners in Benin, Burkina Faso, France, Spain and Belgium.

How did you come up with the idea for the project?

LISELOTTE I did my PhD at ITM with dr. Tania Crucitti. Once the project ended, I took a postdoc position at Ghent University, working with civil engineers on a chlamydia rapid test based on lab-on-chip technology. But when that project came to an end, I saw an opportunity to come back to ITM to work in the Unit of Tropical Bacteriology.

One day, I was sitting at the breakfast table with Professor Jan Jacobs in DR Congo. We were talking about blood cultures. Jan Jacobs asked if, with my background in photonics, I couldn't think of anything to improve working methods. And so the ball got rolling. I went back to my former colleague Professor Roel Baets. He was very enthusiastic to come up with a solution together.

The partners in Grenoble rolled into the project as if by chance. I had contacted them for something else. And I had been toying with the idea of local production for some time.

So it is to your credit to bring everything together?

LISELOTTE Actually, yes, but of course not without the help of my colleagues. I wrote the project out at the beginning of the lockdown, in 2020. I was sitting at home, thinking like so many, "What am I going to do now?" I dreamed of working out a really big project, and just started working on it. My colleague Barbara Barbé joined me and continued to play a very important coordinating role in the project afterwards. It was exhilarating that it could then also be funded!

How did you end up at ITM in the first place?

LISELOTTE I always wanted to work at ITM (smiles). I'm one of those idealists who graduated with the goal in mind: "That's where I want to work!"

From when was that clear?

LISELOTTE I have an adopted sister. She is from India, and when she arrived in Belgium as a three-year-old, we brought her to ITM for a parasite study. I was 14 and totally impressed. Later, I studied biomedical sciences in Diepenbeek. I chose Ghent for my undergraduate studies, with the idea of doing a postgraduate in ITM after. I remember saying on my first application to ITM that I wanted to improve the world. In hindsight, that does sound a bit naive, but I had previously worked in the pharmaceutical industry for two years and I definitely felt out of place there.

What is the next step in the SIMBLE project?

LISELOTTE We will work with McGill University to further develop the blood culture system. McGill has made a low-cost development for antibiotic sensitivity testing. That complements the other two parts of the project nicely. We are also thinking of using AI during growth in the turbidimeter, to start identifying the bacteria already there.

So actually to already be further along in the diagnosis during the first step?

LISELOTTE Indeed ... If that would work, and I hardly dare to say it, the impact on a global scale would be immense. We would then really have taken a big step forward.

And the production?

LISELOTTE Dissou Affolabi is already further ahead locally with scaling up production, but he has that in hand. We have already submitted a project application to expand local production to other countries, but it is difficult to find finances for this kind of project because it is capacity building rather than scientific research.

Become a healthropist

We invite anyone who is passionate about our mission to become a Healthropist. A Healthropist is a philanthropist with a heart for health, someone who believes in ITM's mission to create positive change through science, education and service. Everyone is welcome. The shared vision of global health is central.

Spread the word! Share this story on