"You don't die of leprosy; you die with leprosy."

Prof Epco Hasker is an epidemiologist in the ITM Department of Public Health. Since 2016, he has coordinated research projects to combat leprosy in Comoros and Madagascar. The research he conducts in collaboration with local partners, agencies and charities such as Damien Foundation was recently awarded the Anne Maurer-Cecchini Award.

Many of us know leprosy from stories of antiquity and the Middle Ages. How exactly do you get the disease?

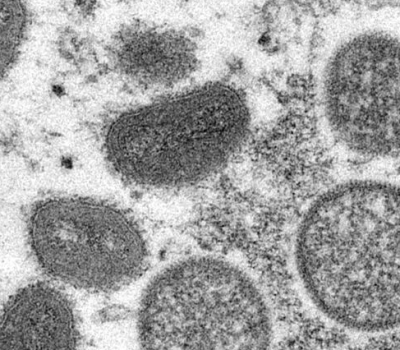

Epco: You get the bacillus that causes leprosy through the respiratory tract. The bacillus starts multiplying and spreading to the surface nerves. The disease affects the skin, peripheral nerves, mucous membranes of the upper respiratory tract and eyes.

It starts with a loss of sensation. For example, if you hold a hot cooking pot, you won't feel it. Or imagine walking around with a pebble in your shoe. The wounds that occur that way get infected. Those wounds worsen and may cause people to lose fingers, for example.

Because nerves control your muscles, you also are afflicted with a loss of strength. You may develop finger contractions (claw hands). If the disease process continues for a long time, the damage cannot be repaired. You don't die of leprosy; you die with leprosy.

How is leprosy treated?

Epco: Only 5-10% of people infected with leprosy effectively get the disease and the incubation period of leprosy is very long. During that period, we can administer prophylaxis. This is a medical treatment that prevents the disease from developing.

However, if someone already has leprosy, they have to be treated with three different drugs for six months to a year. Those remedies work very well. If you catch it in time, everything will be fine. But once deformities have developed, they don't go away.

The BE-PEOPLE project is the successor to the PEOPLE project. What was that project all about?

Epco: In 2016, Damien Foundation in Comoros had been providing quality leprosy care for almost 40 years, but they saw that the number of new leprosy patients was not decreasing. They asked Prof Bouke de Jong and I to develop a scientific project.

So, Damien Foundation asked ITM for help. How did they know they could turn to us?

Epco: Bouke was already involved in projects for Damien Foundation around tuberculosis. I was on a jury panel for them evaluating research proposals. They already had a proposal that dealt with prophylaxis, but it wasn't very good exactly what they needed. I offered to improve that proposal.

Damien Foundation then suggested going to Comoros. After all, there they had a very good team led by Dr Younoussa Assoumani with whom we could work excellently.

We then started a small study. We saw that Damien Foundation had been doing mini-campaigns for several years, installing a medical post at a central point in a village. People with skin problems were invited to visit. That's how they found many new leprosy patients.

You discovered that Damien Foundation had already taken a useful first step.

Epco: Indeed. Two years before our arrival, they had already given rifampicin as prophylaxis to leprosy patient contacts in four villages. I suggested screening the entire population in those four villages to see what the impact had been.

They did that and there turned out to be an awful lot of leprosy there, as much as 2% of the population in some villages. That's a lot, because normally you would expect at most 0.01% of the population to have leprosy. Then we could decide that the mini-campaigns and rifampicin for individual contacts were not enough.

We then wrote a project proposal for EDCTP (funded by the EU). In a district of Madagascar and Comoros, we divided villages into four groups. In the first group, we did only door-to-door screening and treatment of leprosy patients. That was our reference group. In the second group, we provided rifampicin to all household contacts. In the third group, we distributed rifampicin to the whole village. In the last group, we also did a serological test for leprosy infection. If that was positive, we also gave rifampicin.

What was the result of that?

Epco: Where we gave rifampicin to the whole village, we saw about 45% reduction in the risk of getting leprosy, at the individual level, and also at the population level. So, it had an effect, but not as strong as we had hoped.

Why is that?

Epco: It could be that transmission is very high and people are infected with a high dose of bacilli, so a single dose of rifampicin is not enough to eliminate those bacilli. Therefore, we wanted to try something stronger. That is the current BE-PEOPLE study.

In this study, funded by Janssen Pharmaceuticals, we are trying a combination of rifampicin and bedaquiline. Bedaquiline is actually an anti-tuberculosis drug. It was the first new anti-tuberculosis drug for 40 years when it came on the market more than 10 years ago. It is very effective even against multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. The bacillus that causes leprosy and the bacillus that causes tuberculosis are very similar. They are susceptible to the same kind of antibiotics.

The PEOPLE study was awarded the Anne Maurer-Cecchini Award. You say you were only able to get a 45% reduction, which made the results somewhat disappointing, but that turned out to be good enough for the award?

Epco: We received the price for the quality of the study. It was well-designed and well-conducted by a very competent team. But an earlier study in Indonesia, in which an entire island population was given prophylaxis, had shown a much stronger effect, 70-80% reduction. We may get those numbers with the addition of bedaquiline, because bedaquiline stays in the blood longer. Also because we are administering two drugs simultaneously, we expect more effectiveness.

Do you have an idea of the success rate of the new study yet?

Epco: No, we have just finished the first round of interventions. So now we still have to follow up in the 44 villages that are part of the study. This time there are only two groups in the study. All leprosy patients we find are treated immediately, but in the first group of villages we give rifampicin plus bedaquiline to residents who do not have leprosy, in the second group of villages we only give rifampicin.

Professor Bouke de Jong is in the Department of Biomedical Sciences, you are in the Department of Public Health. Is this a good example of interdisciplinary collaboration?

Epco: It's a fantastic example! We each have our own role and together we form a very strong team. Although we both did work together with Damien Foundation before and we are colleagues, we only really started working together for this project.

How did you end up at ITM?

Epco: I took the tropical course at ITM in 1989 and even met my wife there. We then worked abroad for about 15 years. In between, we both took the master's course at ITM in 2001-2002, which is when I met Prof Marleen Boelaert. In 2008, we wanted to come back to Europe. I contacted Marleen and asked her if by any chance she had a vacancy. She immediately wrote back that she did!

That's why her photo is here on your cupboard.

Epco: Yes, Marleen was my role model, absolutely.

What do you hope will happen next within BE-PEOPLE?

Epco: I hope the protective effect still goes up. If it does, I hope this combination will become a WHO global recommendation. But we can't say that yet, because we have to follow up people who have received prophylaxis for three years. And in the next year and a half, we want to screen all villages once again to give prophylaxis to those we missed in the first round.

We foresee the end of the study by 2027, although we would still like to find funding to follow up all villages for an additional year. Then we will also have a long enough follow-up for those who only get prophylaxis in the next year.

I read last week that vaccine against leprosy is being developed.

Epco: That's right, there are two vaccines in development, but they are still in a preliminary stage. We are not involved in those studies. There is also already an old vaccine against tuberculosis, BCG, which also partially protects against leprosy.

A difficult step to eradicating neglected diseases is finding the very last cases. Are you hopeful that the same will happen with leprosy?

Epco: Yes, in a number of countries that is already happening. We are setting up studies there to evaluate whether leprosy is really disappearing, or whether you just miss a lot of patients because the screening system is no longer there or it no longer works as originally conceived.

That's why the collaboration with Bouke's laboratory is very important. They can determine whether patients are infected with the same bacillus, whether the bacilli have the same DNA fingerprints. If they are indeed the same, we suspect a chain of transmission. The geographical area where this occurs then needs extra attention.

How many years will it take before leprosy is out of the world?

Epco: Globally at least another 10 to 20 years, or even longer. In Comoros, we could get very far within five to ten years, but then you have to keep it under surveillance all the time. Doctors and nurses have to keep thinking about leprosy when people come in with symptoms. If the numbers are below 1 in 10,000, the average doctor sees maybe one patient every two years. Chances are they will not make the right diagnosis. We will have to stay vigilant.

Spread the word! Share this story on