The global health predicament after the US funding cuts

When news broke early February that the U.S. would cut its global health funding, the reaction within public health circles was immediate. Especially as key programmes like PEPFAR, USAID, UNICEF’s polio immunization initiative, UNAIDS and the Demographic and Health Surveys project were among those affected. Raffaella Ravinetto, head of the Department of Public Health, vividly remembers the surge of concern that followed.

“There was a flurry of discussions in our Health Systems and Health Policy Research Group,” she recalls. “Everyone reached out to friends and former colleagues in different countries to piece together what was happening. Health systems researchers for instance in Cambodia and Uganda reported colleagues were unable to contact key offices because they had shut down. Conversations with colleagues working in HIV echoed the same concerns. It was a kind of an ad-hoc communication network, where we all compared what we were learning.”

For Kristof Decoster, a researcher in the Health Systems and Health Policy Research Group, the debate unfolded rapidly through his knowledge management work for the International Health Policies Newsletter. “Comments flooded in from different perspectives about what this meant for global health. Including from those who saw this as a potential second wave of momentum for the decolonizing global health movement, following the one sparked by the COVID-19 vaccine inequity. But no one denied that in the short term, and even in the coming years, the consequences would be severe.”

Beside the abrupt reduction or cessation of US funding, there are broader concerns about the future of development cooperation, the funding for which was already shrinking globally. Some other donor countries have also cut their funding recently, though not as abruptly as the US. Almost two months has passed since the announcement, and experts like Ravinetto and Decoster are left grappling with the enormous human costs, and what might come next.

A system on the brink

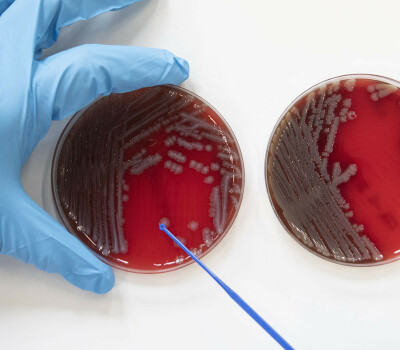

“At first, you worry about big-picture concerns,” Ravinetto notes. “If US funding stops for the TB or HIV programmes, medicine shortages and stock-outs will cause an excess of deaths, and increased disease transmission. But then you start to notice the smaller, yet essential disruptions. The PQM programme of the US Pharmacopeia (USP), an independent, scientific nonprofit focused on supporting quality assurance of medicines overseas, will also shut down its outreach programmes supporting –among other thing- quality control laboratories. It may not seem as urgent as life-saving treatment programmes, but in a functioning system, you need quality assurance, to ensure that you are not only giving ‘medicines’, but ‘good medicines’. ”

As funding dries up, competition for alternative resources will intensify, with donors likely to prioritise health security over other essential health needs. As the WHO puts it, global public health security is about the actions, both proactive and reactive, needed to minimise the danger and impact of acute health emergencies to cross borders and put people at risk.” But this shift, Ravinetto warns, will push crucial yet underfunded areas, like noncommunicable diseases and access for pain relief, even more to the margins. “Who will fund that when infectious diseases are spiralling out of control?” she asks. “Even our research could be seen as less relevant. If diagnostic, preventive, and treatment systems collapse, what’s the point of studying PrEP for HIV or advanced protocols for multidrug-resistant TB? People will ask, 'Why focus on research for the future when people are dying around and among us right now?'”

A costly neglect

Decoster and Ravinetto agree that failing to act today will lead not only to huge human suffering, but also to far greater costs in the future. Public health systems, once dismantled, take decades to rebuild.

“It took 25 years to scale up HIV treatment to reach 30 million people globally. And by combining treatment and prevention, we were approaching a point where you could reverse the epidemic curve,” Ravinetto points out. “If we stop now, reversing the damage won’t take just six months. It could take another 25 years.”

The ripple effects extend beyond HIV. Neglecting tuberculosis diagnosis and treatment today could escalate multidrug-resistant TB into a global crisis. Malaria could spiral out of control, especially if climate change creates the conditions for geographical spread of the malaria mosquito . Whether you have moral or practical concerns, the reality remains: stopping to invest now means losing human lives, as well as paying a much higher price later.

Can we avert disaster?

Despite the dire warnings, solutions remain within reach. In a recently published opinion article in the open-access journal PLOS Global Public Health, Gorik Ooms, Ravinetto, Decoster, and colleagues from partner institutes and ITM alumni in the Global South propose a three-step model to stabilise funding for global health security:

Replenish the Global Fund immediately.

Move towards an assessed contribution model for the Global Fund and other global health initiatives.

Reform their governance structures to make them more equitable, going beyond the classical, but now obsolete, ‘donor-recipient’ dichotomy.

The Global Fund, a worldwide partnership to defeat HIV, tuberculosis (TB) and malaria, and the world’s largest multilateral funder of global health grants in low- and middle-income countries, remains a vital resource. Currently, its three-year funding target is $6 billion per year, a fraction of the world’s combined GDP. If 0.01 % of global GDP were allocated, it would not only replenish the Global Fund but also meet the funding needs for the World Health Organization (WHO) and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. It could even allow for a $1 billion increase in the Pandemic Fund, further strengthening global health security.

However, as Ooms and colleagues argue financial commitment must come with structural changes. The current funding model, which relies on voluntary contributions, creates an imbalance where high-income countries wield disproportionate influence. Transitioning to an assessed contribution system, where all governments contribute proportionally to their GDP, would allow for a more structural ‘Global Public Investment’ approach fit for our times. In addition, equitable governance is a must in global health organisations like the Global Fund, in line with the Lusaka Agenda.

The cost of inaction

Failure to secure stable funding would have devastating consequences:

HIV

The number of people receiving treatment for HIV has risen from 1 million in 2000 to 30 million in 2024. A sudden funding shortfall could result in 6 million additional deaths and 9 million new infections by 2029. Among the most affected would be already marginalised groups, including men who have sex with men, sex workers, transgender individuals, and gender-diverse people.

TB

Tuberculosis remains a global killer, claiming 1.25 million lives annually. If funding ceases or decreases, transmission will go out of control and the spread of drug-resistant TB will escalate, leaving patients without effective treatment globally. TB research, often conducted in the Global South, benefits the entire world, including wealthier nations that rely on breakthroughs made in countries like South Africa.

Malaria

Malaria threatens half of the world’s population. In 2023 alone, there were 263 million cases and nearly 600,000 deaths, primarily among children under five in sub-Saharan Africa. Climate change could exacerbate the crisis, if rising temperatures and shifting rainfall patterns caused a re-expansion of the habitats of malaria-carrying mosquitoes. Continued investments in research, diagnosis, prevention including vaccination, and treatment are critical to sustaining the fight against malaria and preventing the reintroduction of the disease in countries that have eliminated it.

Global problems need global solutions

“As our colleague Gorik Ooms argues, cutting global health funding doesn’t just stall progress. It actively endangers our future,” Ravinetto says bluntly. “ It’s about people going untreated, drug resistance surging, simple infections becoming fatal threats, and diseases crossing borders more rapidly than ever before. If we keep retreating into ‘health nationalism’, where countries prioritise their own health security over global cooperation, future generations will be the ones who pay the price.”

Decoster nods in agreement, emphasising the interconnected nature of today's challenges. “We don’t have the luxury to compartmentalise anymore,” he says. “The climate emergency and global health are deeply intertwined. You can’t fix one while ignoring the other. And while multilateralism hasn’t really led to sufficient results in recent years and decades, for example on the Sustainable Development Goals agenda, there really is no other way to tackle the current polycrisis. Without renewed multilateralism, without true global cooperation in health, we risk sliding into a world where might is right.”

A way forward, if we choose it

Despite their concerns, both Ravinetto and Decoster remain cautiously hopeful. Fear, Ravinetto suggests, may be fuelling the current sense of urgency, but it’s not the only driver. “It’s still possible to change course,” she says. “Our group’s analyses suggests that if we act wisely and quickly, we can still prevent total collapse. The funding gap isn’t insurmountable. What matters now is how the international community will mobilise and use the resources that are available, and how we prepare for the long term.”

Part of that preparation, she explains, lies in shifting the model for funding including a well-planned exit strategy. “Take Gavi, for example. There are plans for countries to gradually take over the costs of some vaccine programmes. It is fair that national governments gradually take on their responsibilities, but we need, structured, phased transitions out of funding. Not shock therapy. We can rethink global cooperation as true cooperation, so it supports countries to become self-sufficient without leaving them in the lurch.”

The problem, she adds, isn’t the lack of money. “The resources are there. What we’re missing is the political will and a willingness to look beyond the next election cycle, understanding that global health is a common good – and a common interest.”

Shocks and shifts

For Decoster, long-term change may lie in the hands of a new generation. “In the next decade, we’re likely to see new leadership emerge, and hopefully, more women in positions of power,” he says. “I’m not saying everything will magically get better, but we might see a shift in how global crises are approached, especially the planetary health emergency, with its interconnected challenges of climate change, biodiversity loss and human health.”

“At some point, the current generation ofleaders will be replaced. And perhaps new generations will then at last be ready to tackle the planetary crisis head on, in a no nonsense way?” However, for now, Decoster admits things are still getting worse on the planet, driven by ecological and political feedback loops.

He also points to Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention as a sign of progress. “During the pandemic, Africa CDC gained real prominence. It was a move towards a more regional, decolonised solution in global health. That kind of leadership, in line with the ‘New Public Health Order’ argued for by ITM alumnus John Nkengasong and other African CDC leaders, local, legitimate, and responsive, in partnership with other actors at all levels, but clearly with African countries in the driver’s seat, is what we need more of. The path forward won’t be smooth. But even in the face of serious shocks, transformation is still possible.”

And so, while the immediate outlook may seem grim, the message from Ooms, Ravinetto and Decoster is clear: hope remains, if we choose it, and if we act on it.

Full article

Ooms G, Assefa Y, Charalambous S, Dah TTE, Decoster K, de Jong B, et al. (2025) Is global health security worth 0.01% of our gross domestic product? PLOS Glob Public Health 5(5): e0004491. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0004491

Spread the word! Share this story on