“My earlier work was focused on specific molecular questions. Here, things open up into reality”

The bookshelves in an office on ITM’s Campus Mortelmans hold equal parts art, science and curiosity. Black-and-white prints from a university museum share space with parasitic illustrations and a Nobel laureate’s book titled Catching the Worm. Here, amid new research projects and meetings, Ciaran McCoy, one of ITM’s newest professors and Head of the Unit of Helminthology, is quietly reshaping the institute’s approach to parasitic worms. We sat down in his office to talk about his work and the fascinating, sometimes terrifying, world of parasites.

“I’m a molecular biologist,” he begins, “and previously I mostly worked on veterinary parasites, parasitic worms. But since moving here, I’ve had more opportunities to work on human parasites and to shift, at least in part, from basic, fundamental research to also incorporate the more applied side of helminthology.”

Ciaran grew up in Ireland. “I grew up on a farm, I wasn’t a real farmer, I have soft hands,” he says with a laugh. Agriculture runs deep in Ireland, and with it comes a strong parasitology tradition. “There’s a strong parasitology group in Belfast that studies parasitic worms,” he says. “The people who were teaching molecular evolution were also studying parasites, so I kind of fell into it that way.”

During his honours project, he became absorbed by the phylogeography of the liver fluke, tracing its ancient spread through Europe alongside cows and sheep. That fascination led to a PhD in Belfast, focusing on reverse genetics and nematode neurobiology, the molecular underpinnings of worm behavior.

Ciaran began collaborating with researchers studying C. elegans, a model worm with a wealth of genetic tools for probing neurobiology. “We had collaborators at KU Leuven,” he recalls. “I spent a year there, and that was a very nice experience as well. I’ve really enjoyed everywhere I’ve been, to be honest. I’ve been lucky with the supervisors I’ve had and I’ve been able to learn a lot.”

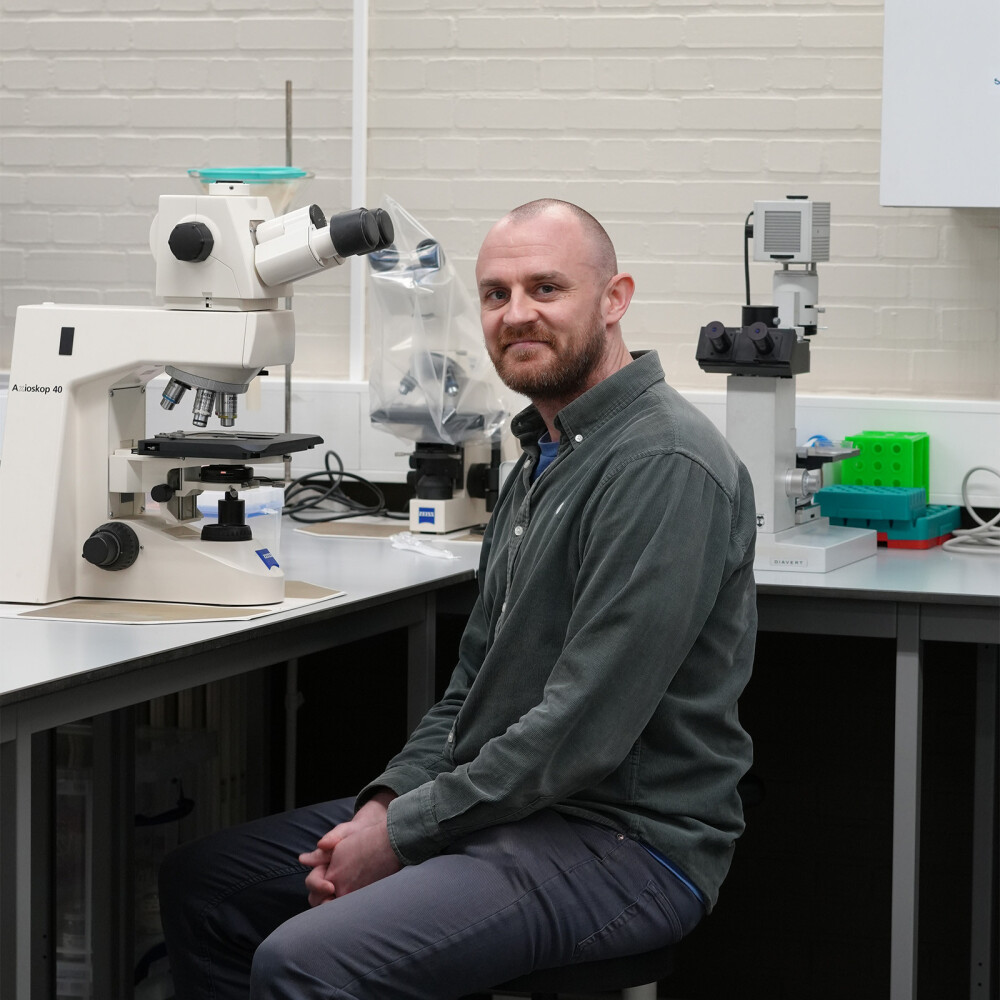

Then, as he puts it, “sort of serendipitously, this post became available while I was already in Belgium. So here we are, and I’m very happy to be here.” He now holds the position of Unit Head of the Helminthology Unit in the Department of Biomedical Sciences.

From grant writing to fox intestines

His time is largely research-focused: writing grants, building new research lines and teaching. He’s helping redesign part of the helminthology module, which is part of the Master’s in Global One Health, balancing his time between research, service, and education.

“Very occasionally I have a completely free day where I can just think, but those are rare,” he admits. “Mostly it’s meetings.”

As one of several newcomers leading new projects, he meets regularly with his team to discuss progress. Though his current role is light on lab work, he still dives in when needed: “looking at snails or fox intestines, lovely things when you’re working with parasites,” he jokes.

Part of his role also connects directly to the National Reference Laboratory for Trichinella. “We don’t look for them ourselves,” he explains, “but we help train scientists in Belgian abattoirs to detect certain parasites.”

Modern tools for ancient parasites

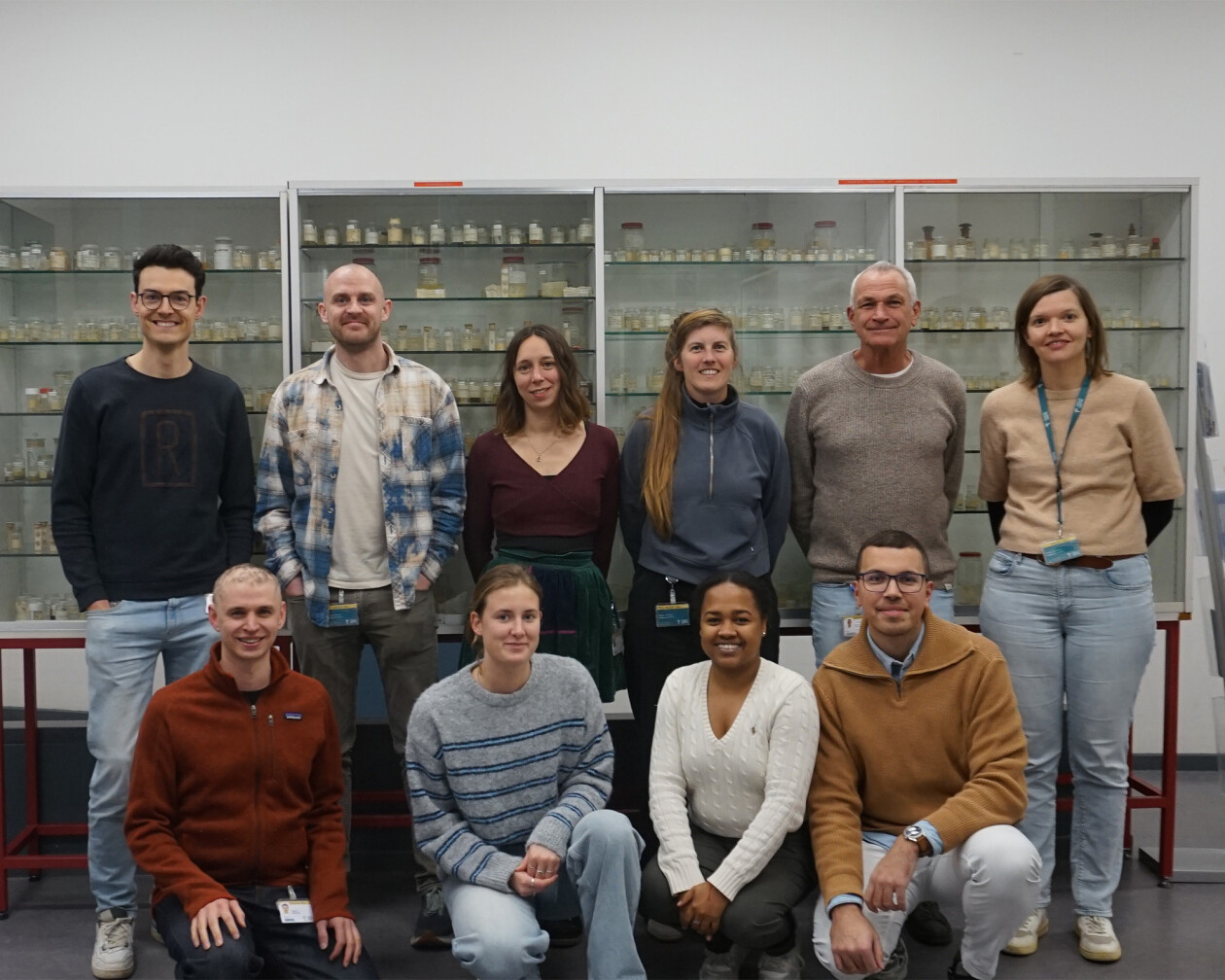

“We’re a strangely diverse unit scientifically,” Ciaran says. “You don’t want to spread yourself too thin, but diversity can be a strength.” Helminthology, the study of parasitic worms, spans two main groups: roundworm and flatworm parasites. Within these groups, ITM’s broader Helminthology Team (including the Eco-epidemiology Unit) has particular strengths in the study of flukes (trematodes) and tapeworms (cestodes), including those that are food- or snail-borne. “Personally, I also aim to deepen our focus on nematode parasite biology, including insect-borne filarial parasites such as those that cause river blindness and lymphatic filariasis.”

“We’re hoping to bring some omics approaches into that, next-generation sequencing, mass spectrometry, functional genomics, that kind of thing.” Ciaran’s aim is to integrate molecular techniques into ITM’s traditionally epidemiological focus, bridging data with biology. “We work on flukes, but also on pork tapeworms like Taenia solium,” he notes, the parasite behind neurocysticercosis, which can cause epilepsy in humans. Even Belgium recently saw a small outbreak among schoolchildren.

Long-term, his team hopes to identify parasite surface proteins that could serve as diagnostic markers or vaccine targets. “There are no vaccines for helminth parasites in humans,” he says. “That’s something to aim for.”

They also plan to collaborate with ITM’s entomologists to explore vector-parasite as well as host-parasite interactions, applying omics techniques to examine the molecular interface between pathogen and host(s). “Helminths are very understudied,” Ciaran says. “They’re classified as neglected tropical diseases, even within tropical medicine, they don’t always get much attention.”

Clever parasites with complex strategies

Two species will take center stage in his lab-based work: Trichinella spiralis and Brugia malayi. Trichinella’s life cycle reads like science fiction. Its larvae penetrate muscle cells and reprogram them into “nurse cells” that shelter the parasite for years, until the host (such as swine or wild omnivores) is eaten. “It’s a food-borne parasite and a fascinating zoonotic one,” Ciaran says.

Equally compelling is Brugia, a mosquito-borne filarial worm that causes lymphatic filariasis, better known as elephantiasis. “It times its appearance in the blood at night, syncing with mosquito feeding habits,” Ciaran explains. “It’s a pretty clever parasite for having only about 300 neurons.”

Collaboration across disciplines

ITM’s Helminthology Unit works closely with epidemiologist and former head of the unit Professor Katja Polman and infectiologist Professor Emmanuel Bottieau, connecting molecular work to diagnostics and disease control. Ciaran is helping to strengthen that pipeline and to build new collaborations with other parasitology-focused units within the department that share similar research goals, and are a step or two ahead.

“It’s a lot more ‘big picture’ than what I’m used to,” he says. “My earlier work was focused on specific molecular questions. Here, things open up into reality.” At ITM, Ciaran sees the opportunity, and challenge, of transforming fundamental biology into applied outcomes. “That’s the advantage of working here,” he says, “and also the interesting part.”

Fascination and fear

Ask Ciaran to name a favorite parasite, and he hesitates. “I’m torn between fascination and terror,” he says. “Their diversity is incredible, and their life cycles are so bizarre. Some don’t always seem to make logical sense from a rational design point of view, but clearly they work.”

He cites Taenia solium and Onchocerca, parasites that can trigger epilepsy in children, as both scientifically fascinating and deeply troubling. The human cost of parasitic disease, he says, keeps the research grounded.

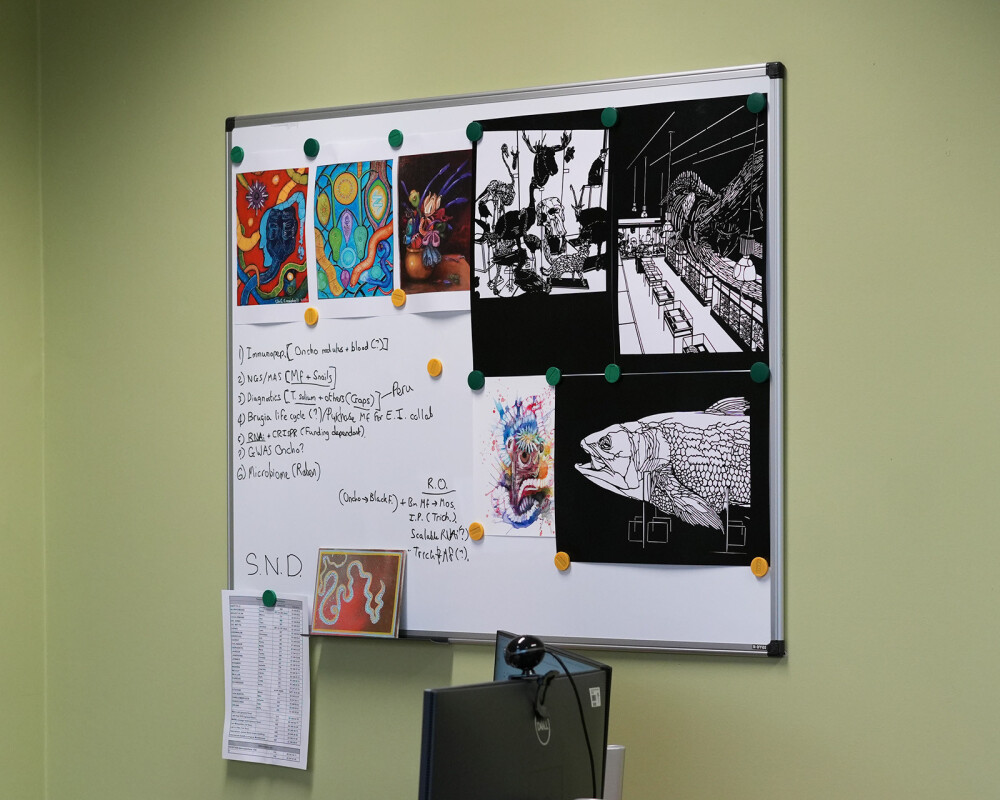

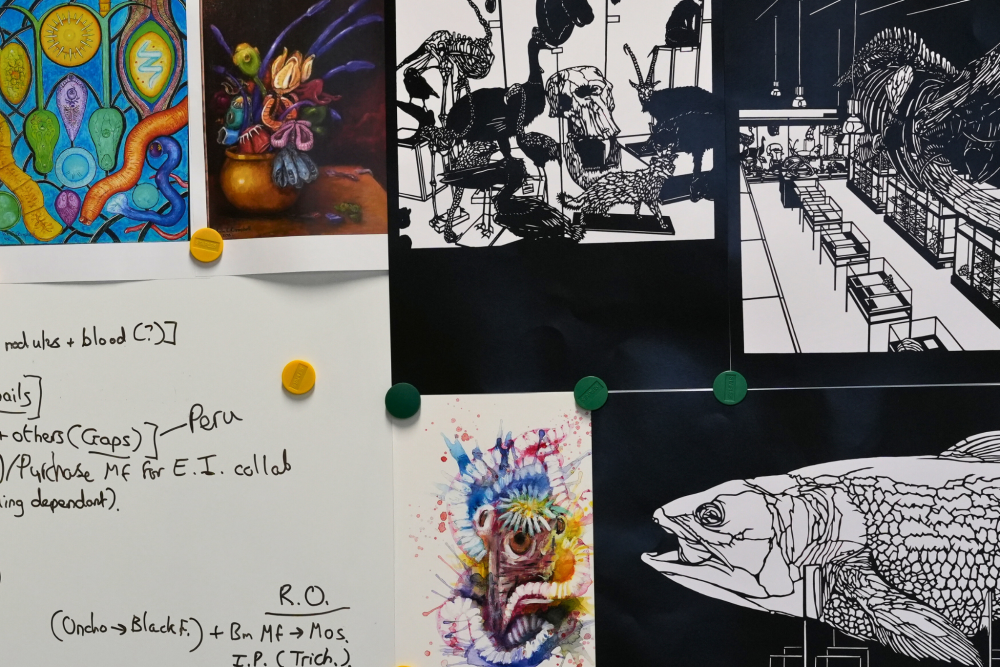

On the walls and the bookshelf

His office walls tell their own story. Black-and-white museum prints from Leuven hang beside colorful drawings of parasites inspired by Van Gogh. One piece, titled Wyrm, merges a worm with a dragon, a nod to the strange beauty of Ciaran’s field.

Among the titles, Catching the Worm by William Campbell stands out. “He believed in keeping things simple,” Ciaran says. “In science today we sometimes use very complex techniques to answer what should still be simple biological questions.” Campbell, who won the Nobel Prize for his role in developing ivermectin, also believed that scientists shouldn’t assume they’re clever enough to outthink nature, or perhaps more that they often overstate the power of the rationale behind the ‘rational approach’ to drug discovery compared with old-fashioned empiricism. Ciaran partly agrees, though he admits AI tools like AlphaFold (a software which predicts protein structures) may soon shift that balance. “Maybe machines are becoming smart enough to help us do that,” he says. “But still, it’s good to keep things simple.”

Science heroes

Science heroes and thinkers outside science both shape Ciaran’s outlook. He cites Sydney Brenner, the Nobel laureate who pioneered the use of C. elegans, for highlighting that technological advances push science forward (often more than specific ideas). “I tend to be more idea-focused,” Ciaran says. “So I try to keep that in mind and push back against my own bias.”

But his intellectual influences stretch beyond biology. He admires Charlie Munger, politics aside, the late investor and thinker known for exploring human misjudgment. “He said, ‘To a man with a hammer, everything looks like a nail,’” Ciaran quotes. “In science, too, you have to be careful not to force your favorite technique onto every problem.” Charlie also highlights that you “shouldn’t torture reality to fit your models”, that you don’t want to be “a one-legged man in an ass-kicking competition”, and that “if you mix raisins with turds, they’re still turds”, among many other wise words worth pondering.

Ciaran McCoy’s work sits at the intersection of molecular precision and messy biological reality. A bridge between genes, proteins and global health. His approach feels both humble and ambitious: keep it simple, think big, but don’t overestimate your capacity to outthink the worm.

Ciaran McCoy

Ciaran McCoy became Professor and Unit Head of Helminthology at ITM in March 2025. He previously worked as a postdoctoral researcher at Queen’s University Belfast, the University of Georgia, the University of Oxford and KU Leuven.

Ciaran aims to study the molecular mechanisms that mediate parasite survival and transmission in both laboratory and field settings, including LMICs and endemic areas in the global South. He collaborates with various partners in the global South to study roundworm and flatworm parasites that primarily infect people in (sub)tropical regions.

Follow Ciaran's research on:

Spread the word! Share this story on