"This map represents what I know": the power of putting Lubumbashi’s maternal healthcare services on the map

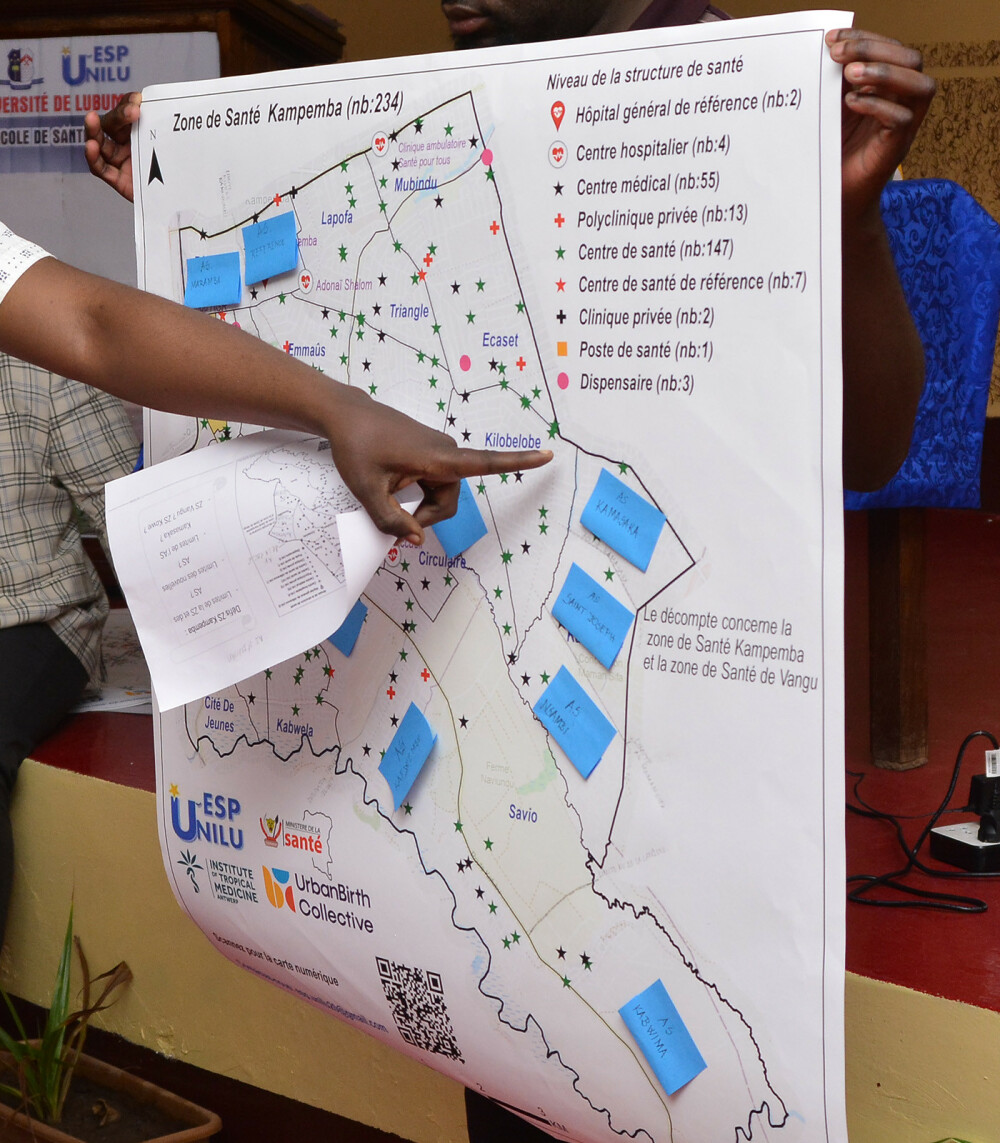

Huddled around A0-size printed maps, over 80 stakeholders and representatives from Lubumbashi’s 11 health zones had lively discussions. Several pairs of hands moved across the maps simultaneously – pointing to health facilities, redrawing boundaries, and scribbling suggestions on sticky notes. It was easy for them to check whether the maps were correct, ITM spatial epidemiologist and researcher Dr Peter Macharia explains: "Because they know their areas like the back of their hand".

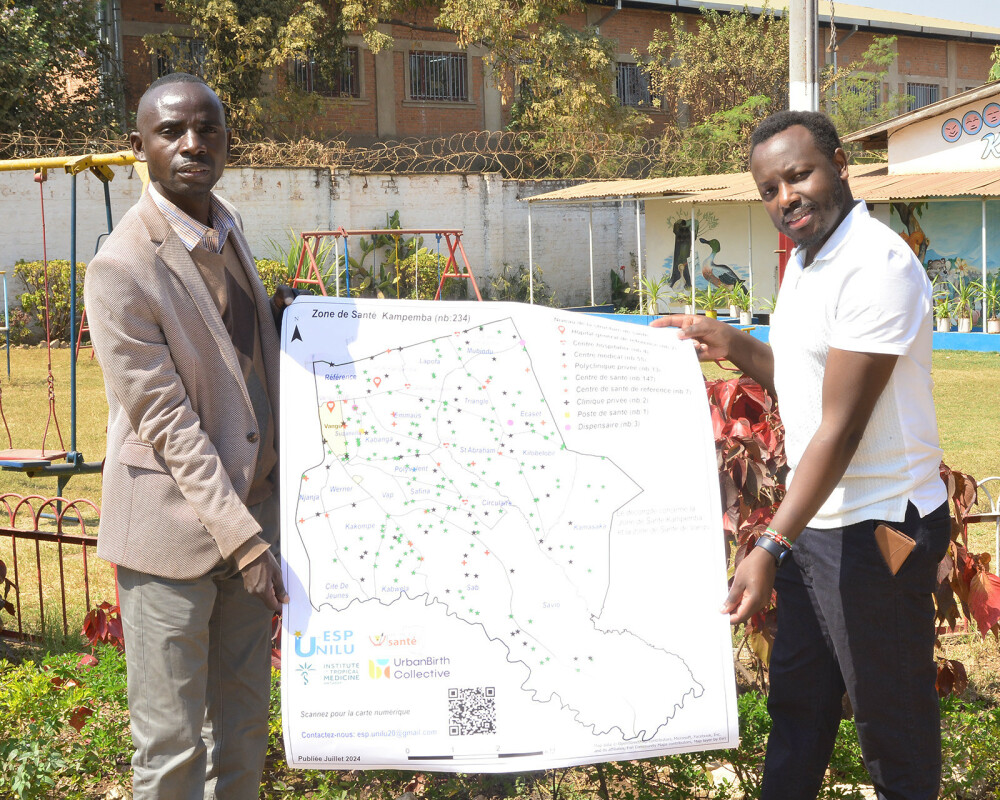

In an urban context like Lubumbashi city, the geographic distance between women’s residence and health facilities might be relatively short. Yet, many pregnant women are still not accessing the care they need, which negatively impacts their health and the health of their babies. The four-year UrbanMat project, a collaboration between ITM and École de Santé Publique of Université de Lubumbashi (ESP/UNILU), aims to better understand this issue. Led by Prof. Abel Ntambue, a team of three ESP/UNILU researchers and 25 data collectors spent four months tracking down the nearly 1.000 facilities providing childbirth care in Lubumbashi. Based on the information and GPS locations collected by the team, Peter plotted maps for each of the city’s 11 health zones.

Peter says: "It’s important to know where these facilities are and what they offer. What is the facility size, what services are available? We really wanted to put this information on the map so the stakeholders could take stock of what they have." When the availability and capacity of services is visualised, it is easier to see where the gaps are. It allows health managers to identify marginalised populations, plan where new health facilities are needed, and achieve a more equitable geographical distribution of more advanced maternal health services, such as c-sections.

It is crucial that these maternal healthcare maps are developed in close collaboration with local leaders and health system managers. Peter explains that a lot of the information required to make an accurate map, such as the exact location of the boundaries between and within health zones, is not recorded anywhere. "That information is only with them, in their minds – they just know that, for example, Avenue Mbuyu Mamie marks the subdivision between health area A and health area B." Therefore, human input is a must. "We need them to validate the maps and confirm: ‘this map represents what I know’".

If stakeholders’ knowledge is not incorporated, the maps will not be used. When visiting one of the health zone offices, Peter found an old map that was made several years ago. When asked whether they used it, the staff said no – the map was outdated and therefore not useful. "When they don’t have a voice in creating or updating it, a map just ends up in a dusty corner." Over time, new health facilities open, others close, and administrative subdivisions may shift. Keeping the maps accurate therefore requires a continuous effort, which is unlikely to happen without local ownership.

Looking back on the stakeholder workshop, Peter is hopeful that these maps won’t collect dust: "I think they owned it, and that they feel they are part and parcel of what is being done". Back at his office, the annotated sticky notes are piled on Peter’s desk. Based on the input gathered, he is now updating the maps. Laughing, he says: "I have a lot of work to do based on the changes they want to see!"

UrbanMat

The UrbanMat project is part of the UrbanBirth Collective. It is funded with support of the Belgian Federal Directorate-General for Development Cooperation and Humanitarian Aid (DGD). It is a collaboration between our Unit of Maternal and Reproductive Health and the School of Public Health of the University of Lubumbashi in the DRC. For more information about the project, read the study protocol and access the first drafts of the maps.

Spread the word! Share this story on