“Outbreaks come and go, but opportunities like this scholarship are rare. Go to Antwerp.”

Placide Mbala-Kingebeni is Head of the Epidemiology and Global Health Division and Director of the Clinical Research Center at the National Institute of Biomedical Research (INRB) in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), a long-standing partner institute of ITM. In 2024, he made it to Nature magazine’s top 10 list of people who shaped science, as the “doctor who raised the alarm about a deadly mpox outbreak that went global”. Just after we recorded our interview, Time magazine included him in its top 100 list of people in health – another international recognition.

You were recently named one of Nature’s top 10 scientists in 2024. How did that feel?

PLACIDE I was honoured and grateful. I thought of the professors, colleagues and mentors who believed in me. This recognition is not mine alone; it belongs to the whole team at INRB who have helped me shape my lab and my department.

Let’s go back to the very beginning. What inspired you to become a medical doctor?

PLACIDE After completing my secondary education, I wanted to pursue something research-oriented that wouldn’t be too much of a routine. I also wanted to find a profession that allowed me to be fairly autonomous. At first, I leaned towards engineering, inspired by my father, who is an engineer with a background in polytechnics. However, at the time, the University of Kinshasa faced a shortage of professors in that field, which led to prolonged academic trajectories. This made me explore other options. Medicine stood out to me, not only because it aligned with my interests, but also because I had friends already in the field who encouraged me to join them.

You completed your MSc in Public Health at ITM. How did you find your way to us?

PLACIDE After completing my medical degree and specialising in microbiology, I began looking for opportunities to obtain a degree from an institution abroad to strengthen my CV. At the time, there was already an established collaboration between ITM and INRB, particularly in the field of bacteriology, between Professors Jan Jacobs and Octavie Lunguya. When I expressed my interest in pursuing a master's degree, both professors encouraged me to apply to the MSc in Disease Control at ITM (one of the predecessors of today’s MPH – ed.). The first time I applied, I wasn’t accepted, which was discouraging. The following year, my professor and mentor Professor Jean-Jacques Muyembe encouraged me to try again.

In early 2015, I was thrilled to receive my admission letter, and along with that, a scholarship. Around that time, I was offered a well-paid position supervising a mobile laboratory in Guinea during the ongoing Ebola outbreak. I faced a difficult decision: take the job in Guinea or go to ITM. When I turned to my professor for advice, he said, “Outbreaks come and go, but opportunities like this scholarship are rare. Go to Antwerp.”

It wasn’t easy to convince my wife, but eventually we agreed it was the right choice for me. I began my master's in August 2015. There were only two Congolese students in the programme: Jean Clovis Kalobu and me. Courses were taught entirely in English, which was challenging. We worked tirelessly, especially on weekends, while classmates went sightseeing. But in the end, the effort paid off.

Did the ITM programme live up to your expectations?

PLACIDE Yes! I learned a great deal, especially in foundational epidemiology, both descriptive and analytical. The late Professor Marleen Boelaert explained these concepts very clearly. In fact, I still have my notes from her classes!

In 2016, you wrote your thesis on the epidemiological surveillance of mpox in the DRC. How has the situation evolved in the past 10 years?

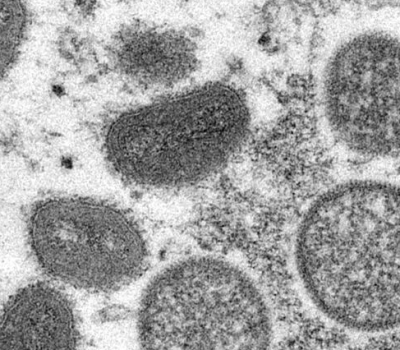

PLACIDE I started working on mpox (previously called monkeypox) in 2008. By the time I arrived at ITM, I already had significant experience in the field. Initially, I wanted to focus on clinical characterisation of it in my thesis, but with guidance from Professors Marleen Boelaert and Veerle Vanlerberghe, we decided to shift toward public health by evaluating the effectiveness of the disease surveillance system.

Back in 2015–2016, the disease was still largely neglected by the global health community. I remember Marleen asking me, “What is monkeypox?” when I first proposed the topic. That said, many epidemiological studies had already been done in the DRC since 2005. I joined the national research efforts in 2008, and my colleagues and I helped establish a CDC surveillance site and later conducted a clinical study with the US Army. We continued case surveillance within the national mpox control programme and conducted various studies with the CDC, ranging from epidemiology and diagnostics to training and vaccine trials. Despite our efforts, mpox remained a neglected tropical disease, with limited funding and attention, even as cases continued to be reported.

Fast-forward to the 2022–23 mpox outbreak, when cases resurged in the DRC and then, for the first time, spread all over the world. How did INRB respond?

PLACIDE INRB has played a central role in mpox research and response in the DRC, long before the disease gained global attention. As early as 2002–2003, INRB was engaging international scientists in collaborative research on mpox. Over the years, we’ve published extensively to highlight that, while often overlooked, mpox remains endemic in several regions, particularly in Central Africa.

Even during periods of global neglect, we remained committed to diagnostic development, epidemiological research, and drug efficacy studies. This was done in close collaboration with partners such as ITM and NIH in the US. Most recently, we made a significant breakthrough with the discovery of a new viral clade, clade 1b, together with ITM.

What does the discovery of clade 1b mean? How is it different?

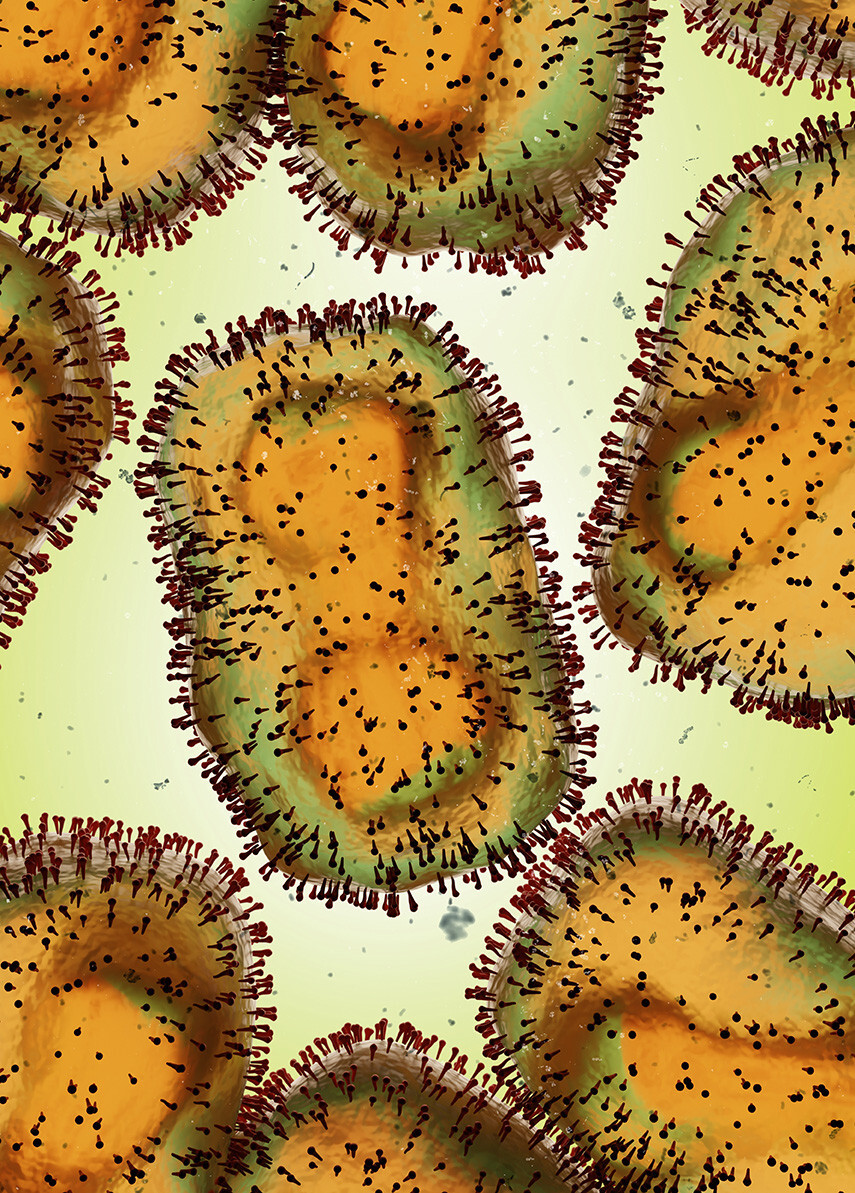

PLACIDE There are two types of mpox: clade 1, mostly prevalent in the Congo Basin and Central Africa, and clade 2, the less severe type, which is prevalent in West Africa. Until recently, mpox was considered primarily a zoonotic disease—transmitted from animals to humans— with only very limited human-to-human transmission, which meant outbreaks were typically short-lived and self-contained. That perception shifted in 2022, when clade 2b was linked to large-scale human-to-human transmission, especially via sexual contact.

The discovery of clade 1b in 2024 is significant because it shows that even the Central African strain, once thought to be strictly zoonotic, can mutate and spread between people. That’s a turning point. We’ve observed infections among adolescents and adults, with evidence pointing to sexual transmission as well. This not only deepens our understanding of the virus but also complicates outbreak control strategies.

Who has the main collaborator been on this research at ITM?

PLACIDE Laurens Liesenborghs, Professor of Clinical Emerging Infectious Diseases at ITM. In fact, it’s more than a professional partnership, it’s a genuine friendship and one of the most rewarding collaborations I’ve had. We began working together on clinical trials for mpox treatment. Over time, we expanded our focus to include epidemiological studies aimed at understanding transmission dynamics, risk factors, and potential reservoirs. Together, we’ve conducted field studies in Tunda, Kamituga, and Kinshasa, to better understand the virus and its transmission dynamics.

Our work began in Tunda, but due to logistical challenges, we moved our operations to Kamituga, where mpox cases were emerging unexpectedly. Laurens visited the sites multiple times, and together we built a local team on the ground. This collaboration led directly to the discovery of clade 1b, and we've continued our research through a strong consortium model, supported by funding and shared scientific leadership.

What do you foresee for mpox case trends in the future?

PLACIDE: It depends on our actions. Right now, infrastructure and diagnostics are lacking. Vaccines are limited, and even in non-endemic countries, mpox still circulates silently. If immunity is low, we may see more outbreaks.

To address this, we urgently need effective treatments, studies on vaccine efficacy, and a clearer understanding of how long protection lasts. Strengthening health systems and investing in community awareness are equally crucial. If we implement these strategies, we might be able to limit the scale and impact of future epidemics.

Spread the word! Share this story on